Now back in print, Kyoichi Tsuzuki reflects on his cult early 2000s photo series capturing high fashion devotees in cramped quarters across Tokyo

While envisioning devoted consumers of luxury fashion, we’re likely to picture the elegant models who appear in glossy magazines, or to imagine fantastically wealthy private individuals or celebrities in a world of abundant beauty and excess. Kyoichi Tsuzuki was shooting Tokyo Style – the now-cult photo book originally published in 1993, in which he lovingly documented the interiors of 100 apartments, condos and homes – when he began gaining intimate insights into how people actually live and the objects they choose to surround themselves with.

“There is a myth that high-end brands are for the upper classes who have high-end lives with high-end husbands or wives, a high-end house with gardens, cars, and dogs or horses,“ says the Japanese photographer. “Photographing the rooms of young people, I found that some of them collect clothes in the same way as others collect books or records. This led me to the idea that the true customers of fashion brands are people who don’t have much money, and sacrifice everyday comfort to spend as much as they can on the latest collections.”

In 1999, born from the realisation that these young working-class and middle-class collectors were the true unacknowledged and uncelebrated devotees of fashion, he began a series of photo essays in the monthly fashion magazine Ryuko Tsushin. Happy Victims ran from April 1999 to August 2006, making it the magazine’s longest-running serial feature. First published in a now highly collectable photo book in 2008, but long out of print, Happy Victims has now been reissued by Apartmento.

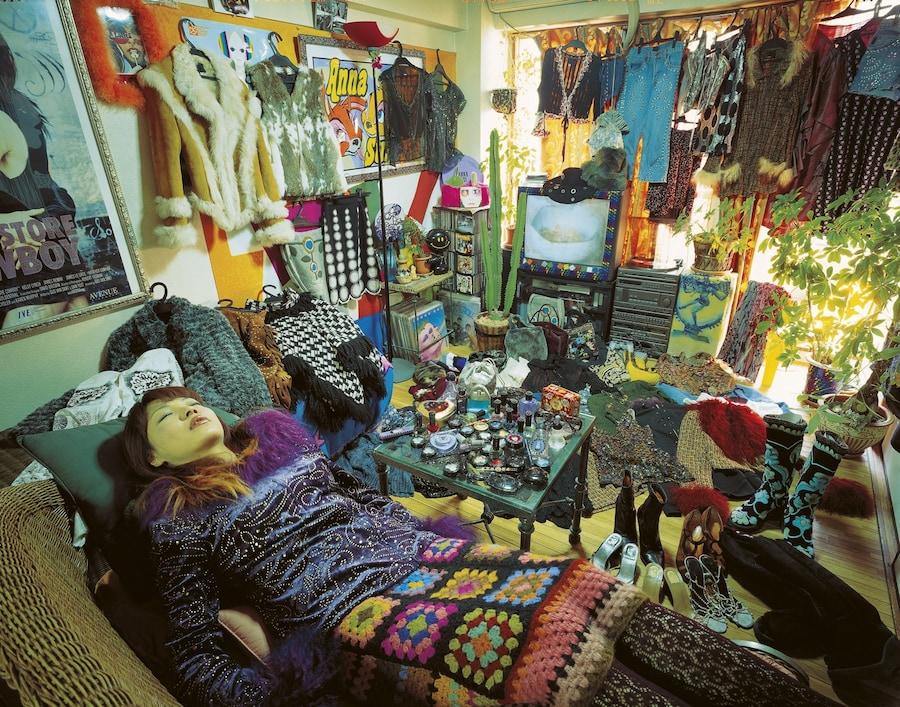

Each instalment features a fashion fanatic in their home with their collection on display. In Tokyo, where space itself is a luxury commodity, there is something deeply poignant about portraits of people whose modestly proportioned living spaces are dominated by their treasured fashion archives, and who are often making many sacrifices in other areas of their lives to acquire new items. Tsuzuki’s subjects are not necessarily buying these clothes to wear at glamorous functions; more often than not, they are buying them out of pure reverence.

Stripped of the other signifiers of wealth, removed from the context of luxury, the garments take on different meanings as cultural signifiers. By removing the supplementary aspirational elements, Tsuzuki’s portraits subvert the mechanism that perpetuates our longing for designer clothes – to possess a few token objects which signify the fantasy lifestyle we can only dream of.

Being so at odds with the aspirational fantasy that underpins our vision of luxury, these devoted collectors are often treated as outliers in the fashion world, shunned by the brands they adore. “It’s strange that the fashion business is hiding its most loyal customers, says Tsuzuki. ”This idea has been my driving force in continuing this project for so long.”

“I remember a young Buddhist monk who was a passionate collector of Comme des Garçons. When I visited his room, the walls were covered with posters, flyers, and collection invitation sheets,” recalls the photographer. “I asked him if, since he spent lots of money on CDG, they invited him to events – but no. No matter how much money he spent on their products, he was never invited to any of their events. So he checked auction sites to find those mementoes.”

It wasn’t always easy to find a fashion devotee willing to be photographed every month. While some of the up-and-coming Japanese brands were helpful, Tsuzuki found that the established fashion houses were obstructive. “Our collectors were never invited to the collections, so it was no use going to the collection venue in the hope of finding someone.” In Tsuzuki’s experience, brands were only keen to reward the dedication of those devoted collectors who conform to type, bringing to mind the adage: “Free to those who can afford it, very expensive to those who can’t.”

“The people who helped us the most were the shop assistants. But in the fashion business, salespeople are at the bottom of the hierarchy. They receive the lowest pay and are forced to buy new collections. It was fascinating to see the small world of low-profile, quiet, devoted collectors and the lowest-paid shop workers.” Tsuzuki concludes. “Without them, no high-fashion business could survive, yet they are never recognised or welcomed.”

Happy Victims by Kyoichi Tsuzuki is published by Apartamento and is out now.