A new book from Thames & Hudson reveals how the trauma and transformation of post-war Japan gave rise to a radical wave of creativity

This month marks 80 years since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki – events that left an indelible mark not only on Japan, but on the global psyche. It also marks the ignition of one of the 20th century’s most concentrated bursts of avant-garde febricity: a period in which Japanese artists, reeling from the trauma of war and occupation, tore away from tradition to invent startling new forms of expression. Casting themselves beyond the confines of a rigid, conformist society, they pioneered radical aesthetics across photography, theatre, dance, illustration and graphic design.

Japan Art Revolution, published on September 25 by Thames & Hudson, is the first comprehensive English-language account of this collaborative movement – one that its creator, designer and author Amélie Ravalec, calls inevitable. “That feeling, of having witnessed the worst of humanity at close range and needing to invent something entirely new from the wreckage, runs through all the work of that era,” she tells AnOther. “These artists were confronting the void together, using the body, language, image and gesture to do it.”

Given the militant origins of the term avant-garde – once denoting the front line of an army – it becomes easier to view these artists’ radical spirit as that of a cultural vanguard waging war against convention. Though much of their work emerged in the wake of political disillusionment and widespread protest – against the US military presence, creeping remilitarisation, and institutional hierarchies – they distanced themselves from the partisan ideologies of their Communist predecessors. Instead, they adopted a broader, existential policy of opposition: socially, morally and philosophically.

“At the heart of this shift was the urge to break free: from tradition, from realism, from the weight of received ideas,” Ravalec reflects. “Artists were no longer interested in representing the world faithfully – they wanted to express something subjective, personal and urgent.”

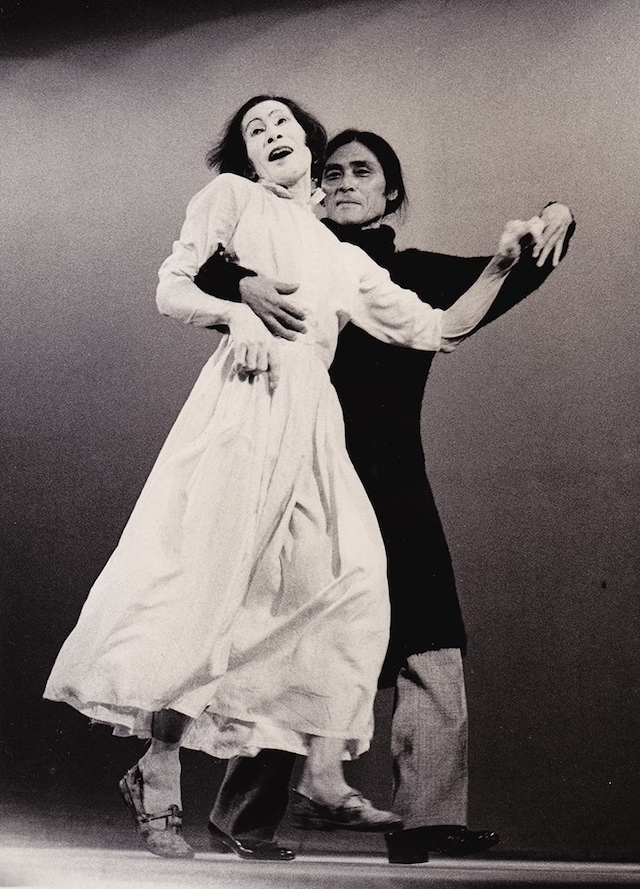

Butoh, a form of Japanese dance theatre, emerged during this period as a true embodiment of the postwar avant-garde’s destructive and visionary impulses. Drawing from Dadaism, Surrealism and elements of sadism, it channelled the deep psychic trauma of war into a dance language of perverse, primal intensity – an apocalyptic afterlife enacted in flesh. The inaugural Butoh performance, Forbidden Colours (Kinjiki) (1959) by Tatsumi Hijikata, was a shocking interpretation of Yukio Mishima’s banned novel of the same name, involving taboo themes of homosexuality, sexual repression, and violence. From bomb-scorched ruins and the dank sewers of the subconscious emerged bodies painted white, heads shaved, twisting, kicking and convulsing through the darkness.

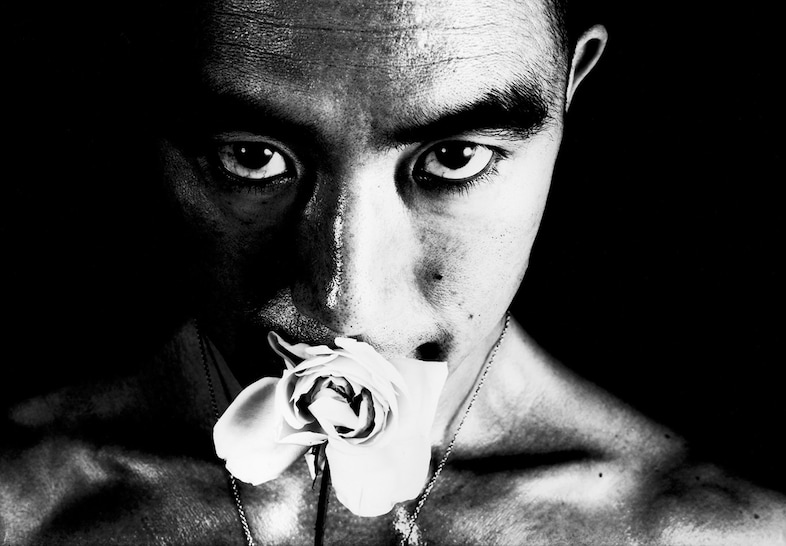

As pop artist Tanaami Keiichi writes in the book, “the 60s was an era of the body.” You feel this with Butoh, but elsewhere too – the body became not just subject, but material. It’s present in Hosoe Eikoh’s iconic photographs of bodybuilder and author Yukio Mishima, where the human form becomes erotic architecture; in the graphic pop art of Yokoo Tadanori; in the rawness of Terayama Shuji’s underground theatre; and in the intense street performances of art collective Hi-Red Center, who left the stage behind and plunged into real life. “At this time art was intense, chaotic, rooted in lived experience,” says Ravalec. “Movement, flesh, ritual, pain and pleasure were integral parts of its vocabulary.”

Historically, Japan has adopted a far more open approach to sexuality than the Christian West. “Bodies were not cloaked in shame and artists of this avant-garde generation drew deeply from that tradition,” reflects Ravalec. “Eroticism became part of the armoury of transgression, a tool for pushing against the limits of what was permitted, of what could be shown, said or imagined.”

One striking expression of this was the ubiquitous depictions of kinbaku, or rope bondage, in the work of artists like Nobuyoshi Araki. Drawing on a centuries-old Japanese tradition where rope holds symbolic and ritual significance, these works explore intimacy, perversity, power and censorship with unflinching directness.

Photography in Japan at this time had shifted radically – from documenting public life to mining the depths of private experience. The 1968 publication Provoke embodied this rupture, positioning photography as an act beyond language – an instinctive, physical response to a fractured reality that refused coherence or control. In 1965, Kawada Kikuji’s revered photobook The Map gleaned beauty in terror as it laid bare the scars of Hiroshima in a series of abstract textural landscapes. However, by the 70s, artists like Daido Moriyama were posing more existential questions. His grainy, chaotic compositions of Tokyo’s street life rejected aesthetic norms, seeking truth in everyday disorder. “For Moriyama, the point was not to aestheticise or assign meaning, but to question what photography even is,” Ravalec says.

The breadth of the artwork represented in Japan Art Revolution resists easy classification, and yet there is a striking sense of commonality that unites its creators. Whether confronting themes of sex, madness or decay, each artist navigates the fault lines between light and shadow, Eros and Thanatos, the personal and the political. Beneath the grotesque, erotic, anarchic top notes lie a profound attempt to make sense of a world that had fallen apart. “These artists weren’t trying to rebuild what had been lost. They were conjuring something entirely new from the ruins,” reflects Ravalec. “I believe the Japanese avant-garde of the 60s and 70s still stands as a raw and defiant testimony to the resilience of the human spirit and to the power of imagination against atrocity.”

Japan Art Revolution by Amélie Ravalec is published by Thames & Hudson and is out on 25 September 2025.