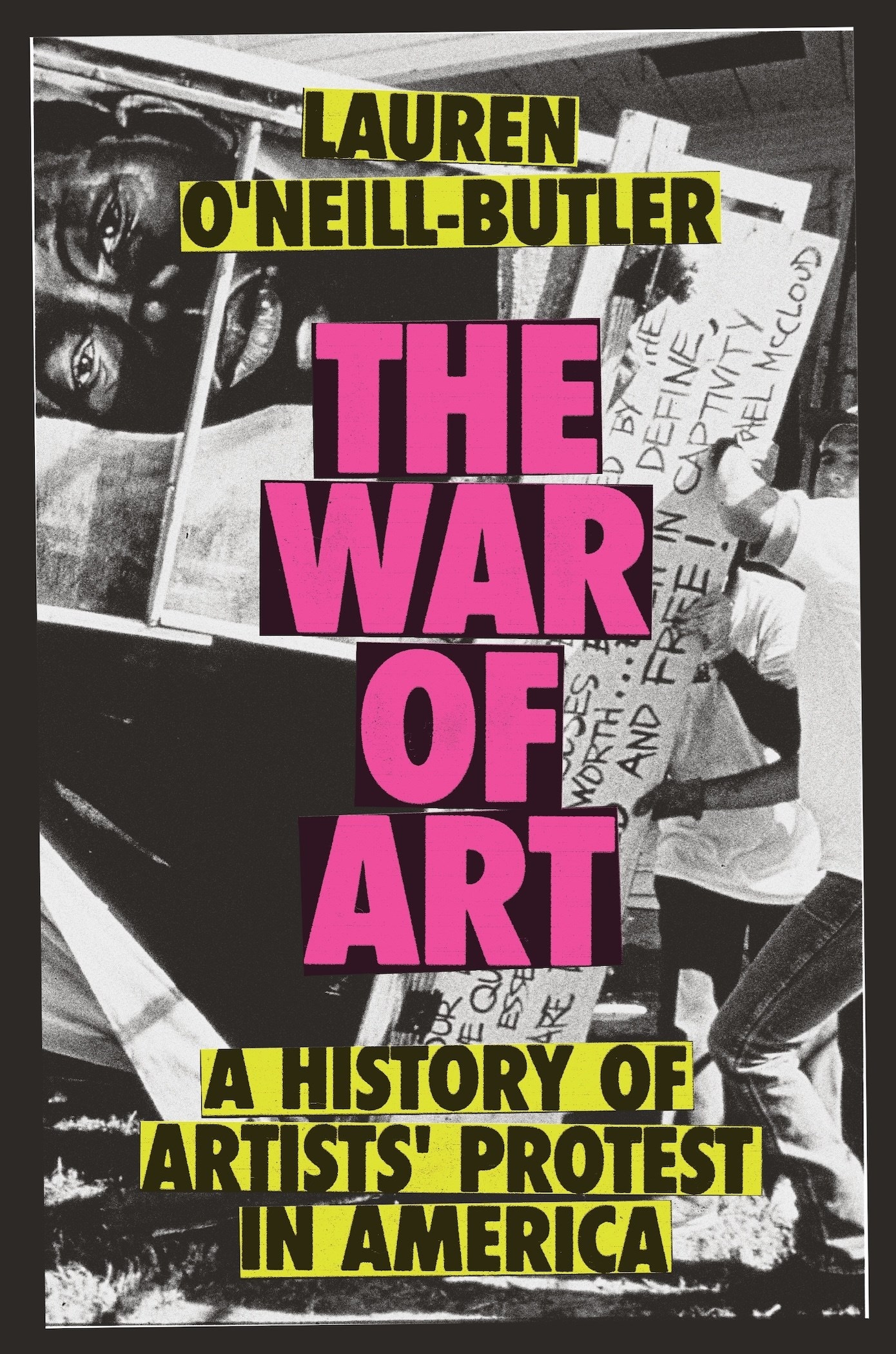

When Lauren O’Neill-Butler started writing her latest book The War of Art: A History of Artists’ Protest in America, she couldn’t have known that it would be released in the first year of Trump’s second term. In such a context, the book feels prescient, daring even. Structured around ten case studies, O’Neill-Butler presents the history of various artists’ protest movements in the US, from David Wojnarowicz’s involvement in ACT UP to the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition’s commitment to prison education, through to Project Row Houses in Houston, an initiative by artists to directly influence the housing affordability crisis.

“I wasn’t trying to offer a manual, because I think those books already exist,” O’Neill-Butler says over the phone from her New York apartment. “I wanted to present a measured narrative that showed successes and failures. At the same time, I did want to prompt people to think, and to let their anger be transformative.” What started out as a few published essays became “a container for rage during the end of the Trump years and into the Biden years”, a way for O’Neill-Butler to trace exactly how artists had previously responded to restrictive and dehumanising political realities and the lessons that their experiences might impart to artists today. “I didn’t think about it coming out this year under this administration, but I hope it feels like I set some foundations. The hope was to show the history and how these artists portrayed a better future, didn’t dwell on an unjust past.”

From her own early involvement in activist scenes in Florida to her later interest in art history, this is the book that O’Neill-Butler says her younger self would be proud of her for writing. Here, she talks about the longevity of activist projects and the importance of constructive conflict.

Jemima Skala: You make a distinction between political art and activist art. What is that distinction for you?

Lauren O’Neill-Butler: What I’m saying is that political art is the ideas, and activist art is the coalition building, building something transformative. Activist art is thinking about the world that we could have. I say in the book that activist art is always political, but political art is not necessarily activist. Rick Lowe [of Project Row Houses] and Nan Goldin’s work with PAIN, you see their individual practices in photography, painting, but it’s not the activism. The activism is informed by the meticulous aesthetic decisions that those artists have always made. That’s why it really works, because artists can bring something different that thinks about aesthetics, community building in a different way, society ... they bring something else, so the activism is very different from the other kinds of housing activism or opioid addiction activism.

JS: Would you describe Project Row Houses as art, then?

LOB: I tend not to think of it as art but as artists doing things. It’s a side of their practice. With Project Row Houses and Rick Lowe, I wanted to show that that’s a natural extension of what he does and what he’s always done. He began by making these large painted maquettes that would go into installations outside, speaking to police brutality in the early 90s in the South where he’s from. That naturally led to coalition building. He eventually left PRH to go back to painting, but the painting reflects what he did with PRH. The way that activism and the art practice run on parallel tracks for most artists, and the art they make isn’t necessarily the activism – it’s the same with Nan Goldin – but they inform one another.

JS: You highlight the importance of the collective, but there’s also a few different individual figures in the book, like Agnes Denes and Edgar Heap of Birds.

LOB: With Edgar Heap of Birds, I wanted to give an example of someone who has a sense of collectivity ingrained in him. He speaks in the ‘we’. As he said to me, ‘We did this activism before, we do it now, and we’ll do it later.’ He was speaking about this long intergenerational Indigenous upbringing and knowledge.

“Activisms expire, and that’s a good thing: you want it to expire. You want the anger to transform” – Lauren O’Neill-Butler

JS: A lot of these initiatives shutter after a few years. Is that just a pattern or is there a way to future-proof these things for a longer lifespan?

LON: Activisms expire, and that’s a good thing: you want it to expire. You want the anger to transform, like it did with PRH where it went from a grassroots coalition into a mega non-profit. In some cases, the activism fizzles out and it takes decades to see the fruit of the labour. With a group like Women Artists in Revolution, they were only active 1969-1971, but what they did had a tremendous effect later down the line. You see a lot more representation of women in museums because of the things they did. Groups do tend to fizzle out. It also depends what they’re protesting; with WAR, it was very focused on getting women into this particular Whitney Annual before it was the Biennial, and once that happened, they all did other things. They splintered again and created more, different activisms from that point. It transforms and sometimes it just ends.

JS: Another thing that came up a lot was money in activist art, and just using what you have around you to create something.

LON: For example, Fierce Pussy is very cash poor. They use museums to create posters so people can take them for free, but no one is making money on activism; in fact it’s the opposite. Edgar Heap of Birds uses the money he’s made from his art practice to create an Indigenous community-led part of a gallery at a university where he went to school, or to create scholarships. That’s philanthropy as activism. All the artists that I look at have practices outside of activism. Nan Goldin, for example, has done very well as an artist, but she leveraged her work and star power to make the activism work. In fact, the activism is like working against the artist making money in some way; she had to put her whole practice on the line and challenge the collectors and museums who had her work.

JS: What’s the main thing that you’d like for artists to take from your book?

LOB: Artists told me they did what they did because they didn’t have a lot to lose. If you already have nothing to lose, then just do it. In this book, I’m trying to recount history not as a memorialisation but as a blueprint. Look what these artists did, why not just do it? People live a long life. If you take the challenges when you’re young, you might see the challenges play out. There’s also a lesson in not being afraid of conflict. With the groups I mention in the book, people had conflict but they kept going. They weren’t afraid to be having heated conversations about things.

The War of Art: A History of Artists’ Protest in America is published by Verso, and is out now.