Now on show in Athens, the South African artist’s new exhibition features probing depictions of motherhood, female strippers at work, nudity and what it means to age

In May this year, Marlene Dumas became the most expensive living female artist at auction. Miss January (1997), a purple-tinted portrait inspired by an image of a blonde in a porn magazine, sold for $13.6 million including fees at a Christie’s evening auction, overtaking Jenny Saville’s former record (approximately $12.4 million for Propped, sold at Sotheby’s in 2018). Speaking on a sweltering day in June in Athens, where the artist is opening her latest exhibition, Dumas is asked how she feels about being the most expensive female artist alive. “I’m not like Trump, who thinks there are only two genders: men and women,” she says, politely sidestepping the question. “It’s a funny position to be in, because in my generation of artists, with people like Jeff Koons, their prices were much higher.”

This matter-of-fact, subtly feminist remark comes as no surprise. Over the past four decades, the 71-year-old South African artist has explored the human condition in her drawings and paintings through a distinctly feminine lens, depicting birth, death, sexuality, violence and the passage of time with an unwavering, hypnotic intensity. Dumas’s new exhibition, Cycladic Blues at the Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens, curated by Douglas Fogle, is equally preoccupied with what it is to be a woman, with the artist’s probing depictions of motherhood, female strippers at work, nudity and the ageing body. In life and in art, Dumas does not beat around the bush; instead, she gets straight to the heart of complex and confrontational subjects. In the introduction to the exhibition’s accompanying monograph, the artist writes, “This is a book for all times; from being born, being young, being attractive and seductive, being betrayed and attacked, to being old and trying not to die.”

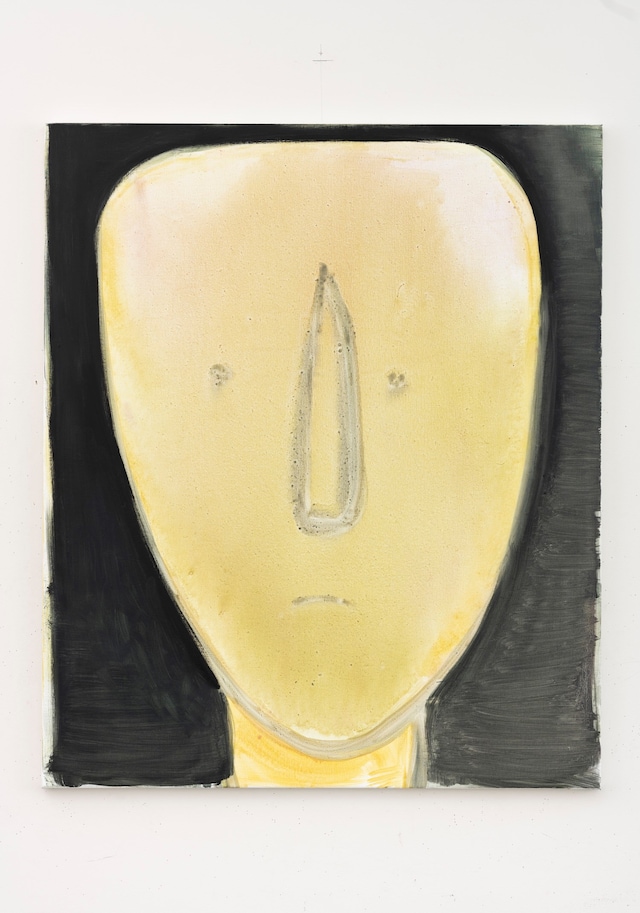

With over 40 paintings and works on paper, ranging from 1992 to the present day (including two newly commissioned paintings), the exhibition puts Dumas’s work in dialogue with a handful of archaeological artefacts from the museum’s collection, handpicked by the artist herself. These ancient figurines, which range from the Late Neolithic period to the Cycladic Bronze Age, elude easy description, as their original purpose is still unknown; instead, they work as enigmatic accompaniments to Dumas’s work, with the human form distilled down to mere shape and form until it reaches near-abstraction. These mysterious sculptures have had an immense impact on modern art, inspiring artists like Picasso, Brancusi, Modigliani and Henry Moore. As Dumas says of their appeal, “These works have a timeless quality, as if freed from our human prejudices.”

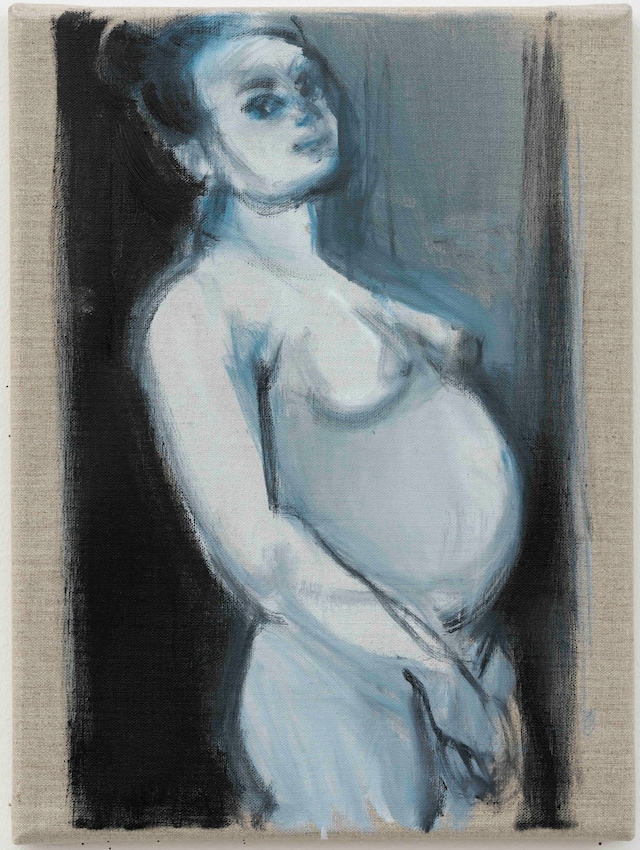

This dialogue between ancient and contemporary is exemplified in the exhibition’s titular painting, Cycladic Blues, a melancholic painting of an ancient figurine’s face, its features rendered in comically simplistic form. The title of the painting – and the exhibition at large – alludes to the artist’s wider themes: blues as a colour, as a musical genre, and as a feeling. Much of the work on display here is shot through with the colour blue, adding a mournful mood to the artist’s work. It’s there in the soulful portraits of donkeys (Donkey daytime and Donkey nighttime, 2021), in a portrait of the artist’s pregnant daughter, her belly swollen with the promise of impending life (Helena Michel, 2020), and in two remarkably simple yet powerful still lifes that luxuriate in the colour blue, (Bottle, 2020) and (Candle, 2020).

Blue reaches its most potent form in two of the most provocative works on show, Immaculate (2003) and Two Gods (2021), each depicting female and male anatomy in surprising ways. Immaculate is a play on Gustave Courbet’s infamous L’Origine du monde (1866), a sumptuous painting of a woman’s legs spread apart on a bed. Dumas’s version is a more sombre take, less eroticised and more matter-of-fact in its depiction of a woman’s vulva and breasts, exectuted in greyish-blue tones. Dumas has said of the work, “It’s so sad. As if no one ever entered here. As if no one ever returned from there. As if it has never been used. As if all colour has gone from the inside, has been drained. This is not the origin of the world. This is the end of the world.”

Two Gods sees two penises writ large on the canvas in blue-black as disembodied, monumental sculptures. Dumas has said this work came about spontaneously, as she poured paint onto the canvas with no preconceived idea of how it would end up. The final result, however, stands as a satirical testament to men and patriarchy. “Eventually, they became these beautiful monumental male sexual organs,” says the artist. “Unfortunately, one cannot help but think of the ugly, egocentric political state of the world, as some male world leaders yet again think they are God’s gift to the world, or rather, gods themselves. I will deny them the pleasure of naming them.”

Themes of sexuality and the erotic continue in the next room, with Dumas’s remarkable and robust paintings of female strippers in Amsterdam made at the turn of the century. Working from Polaroids taken by the artist – she primarily works from photographs, instead of from life – Dumas’s painting Leather Boots (2000) is a masterclass in framing, capturing a stripper mid-squat, frozen in movement against a plane of pink and yellow colour that reverberates off of her naked flesh. High Heeled Shoes (2000), a portrait of a stripper taken from behind, is executed in rough, dark brushtrokes, capturing the illicit, late-night mood of the scene at hand. In 2000, the artist collaborated with photographer Anton Corbijn on a joint exhibition called Strippinggirls at SMAK in Ghent, continuing to explore her ongoing relationship with photography.

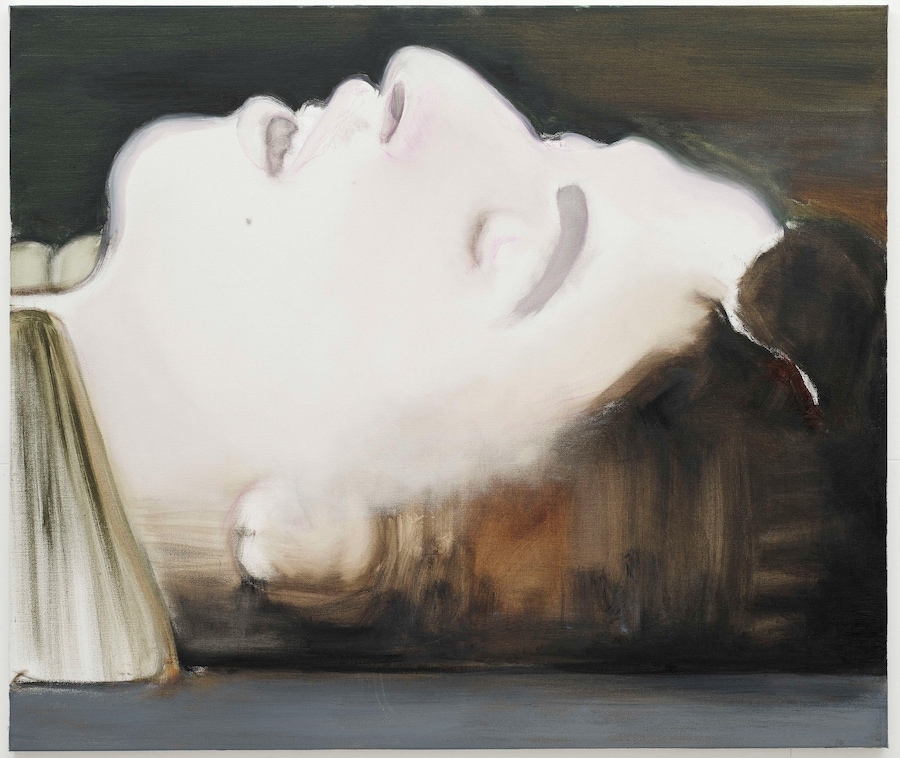

Despite the vitality of the works, the spectre of death still haunts the show. Skull as a House (2007) is a sentimental painting of the skull as the harbinger of the mind, and asks what is left of a person’s consciousness after death. Alfa (2004), a haunting painting created from a photograph in a newspaper of a young dead Chechnyan woman who was part of the Moscow theatre hostage tragedy in 2002, is a ghostly image of mortality, with subtle traces of pink paint on the eyelids and edge of the face suggesting the flicker of a soul recently departed. Unveiled here for the first time, two towering abstract paintings – Old and Phantom Age (2025) – depict the figure of an elder woman, based on an image of a Roman copy of a Hellensitic sculpture called The Old Market Woman. “Being old can make one feel bad and sad,” says Dumas. “[But] to my joy, I was told that this ancient lady, my muse for the night … was apparently an aged courtesan on her way to the festival of Dionysus, the god of wine!” Executed in green and fleshy pink, the spectral figure in these two paintings bends with age. Dumas has likened them to self-portraits; time may march on, but there’s no stopping this prolific artist.

Cycladic Blues by Marlene Dumas is on show at the Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens until 2 November 2025.