Michelle Tea’s Valencia starts with a breathless declaration of love. Maybe not love, but obsession, a feeling so “huge”, “hot” and “wet” that it consumes your heart like a thick fog. The object of Tea’s affections is introduced to us simply as What’s-Her-Name – because when you’re a 25-year-old lesbian, writing from the frontlines of San Francisco’s 90s queer scene, love can come at you fast. “I was an artist, a lover, a lover of women, of the oppressed and the downtrodden, a warrior really,” Tea writes, the lines crackling with ferocity. “I should have been somewhere leading an armed revolution in the name of love.”

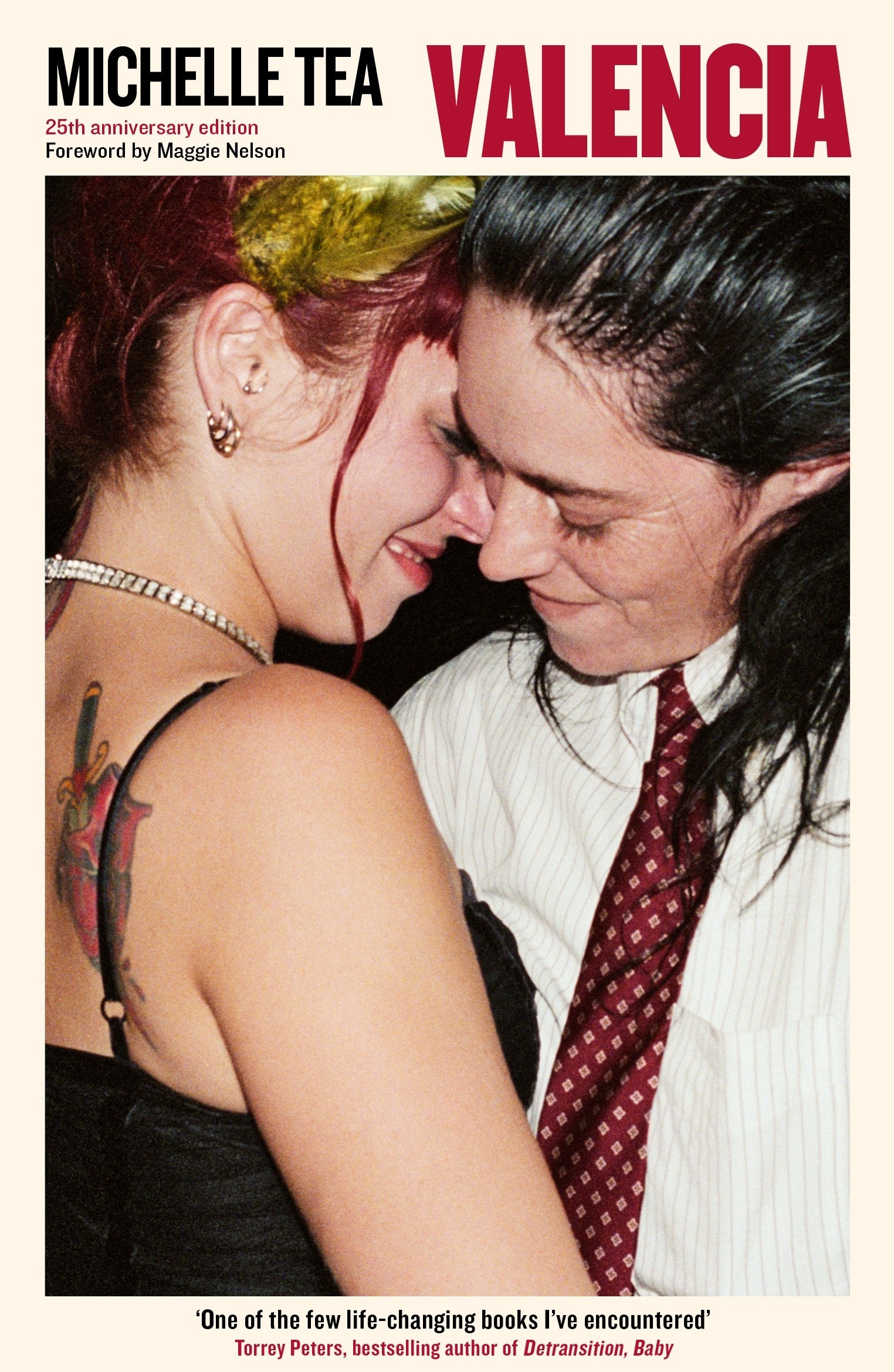

Valencia is a cult classic, a white-knuckle ride through a hugely significant moment in queer history. Released in the year 2000, it is a time capsule of the Mission District in the late 90s: its characters have “Bacchanalian” orgies, make anticapitalist zines on Xerox machines, and do astrology-themed stick-and-pokes in smoky house parties. Hearts stretch and snap like elastic, nights are mangled by mushrooms and meth.

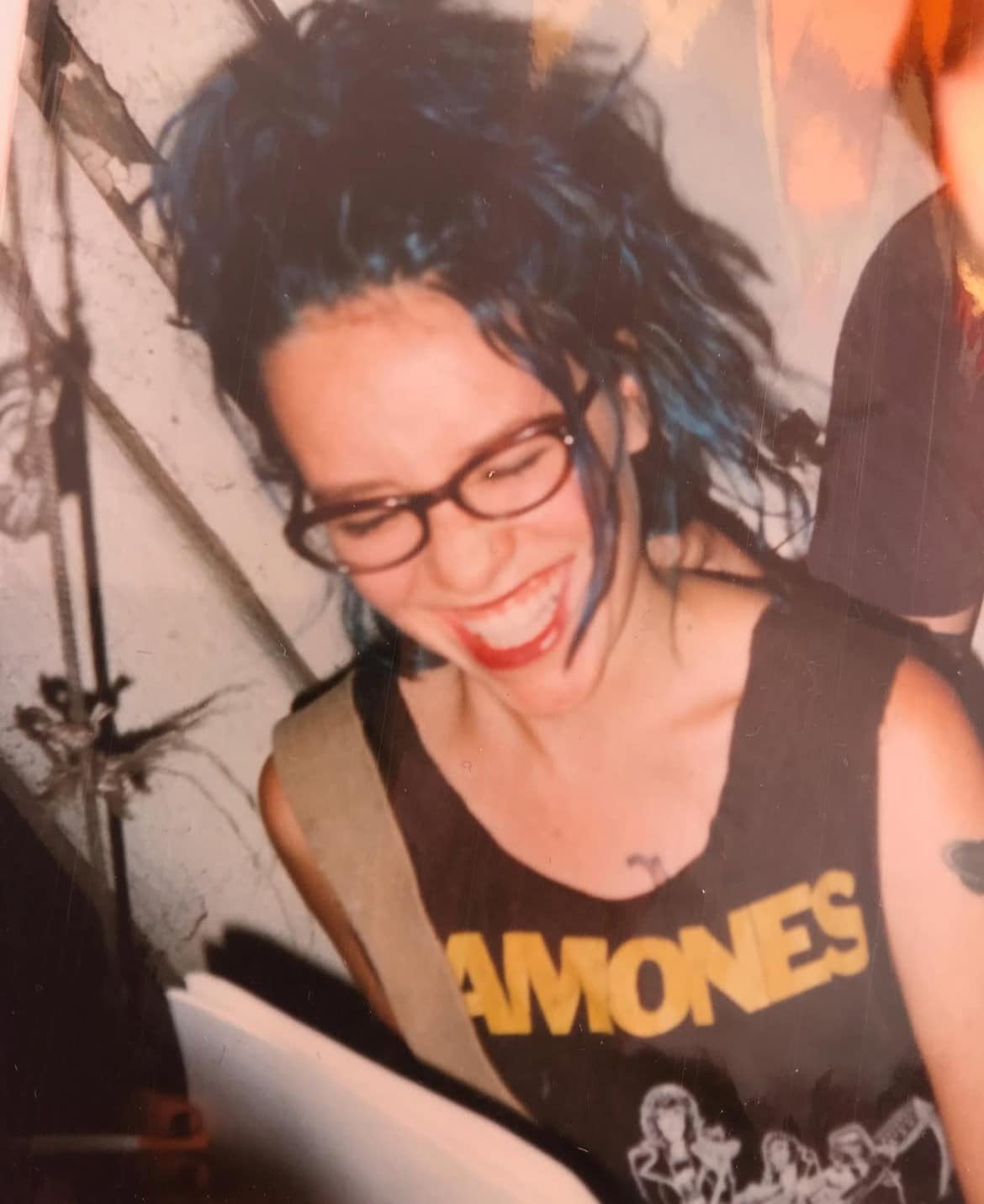

Tea – a beloved memoirist, author and activist – has described the book as a snapshot of her “25th year on earth, written not how it happened but how I felt it happened”. She wrote it compulsively, in the moment, taking out her notepad at every available opportunity. “This desire to tell my story was alive in my body in a way that felt very ferocious,” Tea says today, speaking to me over Zoom from her home in LA. “All I wanted to do was just go out and sit in a bar until they kicked me out, and just write into my notebook.” The result, as Maggie Nelson writes in the introduction to Valencia’s new, 25th-anniversary edition, is a “missive sent straight from the mayhem”, which perfectly captures the rush of “being young, being high, being in love and becoming a writer”.

But Tea’s career stretches far beyond Valencia. As a writer, she is extremely prolific, publishing multiple memoirs and novels, as well as more esoteric self-help offerings (she is a seasoned tarot reader and magic practitioner, and has published guides on both topics). Her fizzy, galvanising optimism, which pops on the pages of Valencia, has also seen her become one of the most influential contemporary voices in LGBTQ+ activism. To name just a handful of examples: as well as touring America with her decades-old spoken-word collective Sister Spit, she also started the politically contentious Drag Queen Story Hour, and in 2023 launched the queer nonprofit publishing press, Dopamine Books, with the support of Semiotext(e). Despite many lifetimes of achievements, she remains warm, humble, and future-focused. “It’s just amazing that something I wrote when I was 25, living arguably a very niche life, has persevered and is still considered relevant in some way,” Tea says of Valencia, with genuine incredulity.

Below, she reflects on the 25 years since its release.

Dominique Sisley: How do you feel about the contents of Valencia, 25 years later? Do you recognise the woman who wrote it?

Michelle Tea: The thing that made the book unique was that I just followed every tangent. It’s the interior monologue of somebody who was very high energy and excited about life in this really young way, where everything is new.

DS: It feels so immediate, like you weren’t overthinking or labouring over the words at all.

MT: Completely. I don’t really labour over my work that much in general. I do tweak and edit now, far more than I did when I was younger, and I’m very careful about how I represent other people. But I don’t care about how I represent myself – I just sort of fling it out there and see what happens.

DS: That feels rare now. I feel like people are much more vigilant about how they come across, there’s more self-censorship.

MT: There are certainly things I say in the book that I wouldn’t say now – I was 25, and it was the 90s. It’s not an excuse, but what you see is the entirety of my consciousness as it was in that moment. For the most part, I can get behind it. I know people are very scared to make public mistakes, because the public can seem so unforgiving and merciless, but that’s just a result of the intense need for social justice. People are fed up, as everybody should be. At the same time, I also feel like it’s OK if I make a mistake, I can apologise. Careful writing has never interested me. I’m far more interested in writing that takes chances and is risky.

“There are certainly things I say in the book that I wouldn’t say now – I was 25, and it was the 90s. It’s not an excuse, but what you see is the entirety of my consciousness as it was in that moment” – Michelle Tea

DS: You’ve spoken before about the cyclical nature of political movements. Do you feel we’ve made meaningful progress since Valencia was first released, or are we still caught up in the same conversations?

MT: We are seeing history repeat itself again and again. And at the same time, things are quantitatively better than they were in the 90s. Overall, I think queer people are safer, especially in progressive cities. I don’t know that we’ve had a government that [was so focused on] oppressing and obliterating queer and trans people before, but it‘s a result of how much progress we’ve made. The government was trying to oppress and silence queer people in the 90s, and today, they’re trying to legislate trans people out of existence, so the battleground has shifted. It’s very scary because trans people require different care than cisgendered queer people do, so the stakes feel a little bit higher: their very basic human rights [like medical care] are being threatened. It’s wild. Trans people have never been so visible, and had so much public support, and also never been so demonised.

DS: We’ve just moved through an era of pinkwashing, where a lot of queer art was co-opted, sanitised and stripped of its radical edge. In your view, what does truly radical queer art look like today? How do you define radicalism now?

MT: For me, radical queer art is just art that tells an uncompromising truth about queer experience. And sometimes the queer experience is the fact that you just want to get married and cuddle up with your partner, you know? I don’t like people going out of their way to try to be so radical or edgelord about it, it’s a very varied experience. But the real gift of being queer is that being cast out of the culture means you get to create your own culture, and you get to see all the hypocrisies, all of the problems, and how they’re all interconnected. You get to see the intersectionality of oppression from your outsider’s vantage point. You also get to reinvent what family, kinship, gender and freedom look like. A lot of people don’t realise how programmed they are. It sometimes takes somebody from a radically outside perspective to just bonk them gently on the head and be like, ‘You don’t need to live your life like that’.

DS: You’ve talked before about getting older and the risk of becoming boring or complacent, and the importance of holding on to that punk spirit. But how do you actually do that? How do you hold yourself accountable?

MT: Well, nobody’s wild 365 days a year. People go through different seasons and chapters of their lives. There was a moment when I was feeling very conventional: I had a baby, and that’s the kind of experience that requires you to bring it down a little bit. You have less time, you have less energy, and the stakes get really high. So I think it’s just about being true to your desire, and always checking in, [asking yourself] ‘is the way I’m living still the way that I want to be living?’ It’s just about being authentic to who you are.

DS: As you get older, living authentically can become more complicated. The common narrative is that it gets easier with age, but I think in some ways it gets harder: it gets easier to sleepwalk through life, to numb yourself out on routine and stop taking as many risks.

MT: We want different things at different times in our lives, and some of those things have an element of permanence to them, which means they are harder to get out of. If people want to get married and have a home, these things are very binding. People can end up feeling a little bit trapped in their decisions, and then have that midlife crisis, right? People are raised thinking their life should have a certain shape. You’re allowed to be a little shapeless when you’re younger, but there’s always this expectation that you’ll get more into shape as you get older. It’s a false narrative. Not everybody wants that. Some people just want to be hobos for their whole life, you know? No one’s ever trapped. It’s an illusion, you can always make changes.

DS: How has becoming a mother shifted your creative sensibilities and the way you approach your work?

MT: I just have so much less time for it. I’m really lucky because I have my child every other week. When my ex and I divorced, it initially felt completely devastating, and then very quickly I realised it was amazing. When he comes to me, I’m just ready to be completely available to him. I’m really lucky that my life can be structured in that way. But it is harder to get things done. It’s also made my financial situation much more acute. I was pretty OK with just scraping by and living a very low-income, punk life [before him], but I don’t want him to be living hand-to-mouth. Fortunately, I’ve been able to sell books and support us, but that means being guided towards work that is more commercial, which is not where my heart is. I hate thinking about being accessible. So yeah, my writing’s probably got worse since I’ve become a mother. [Laughs].

DS: OK, but it technically made you more successful ...

MT: But not necessarily creatively satisfied, right? I mean, I love being commercially viable, no one’s more shocked [about that] than I am.

“People get raised thinking their life should have a certain shape. You’re allowed to be a little shapeless when you’re younger, and you’ll get more into shape as you get older. It’s a false narrative” – Michelle Tea

DS: I feel like one of the reasons you’re so prolific with your work is that you can step outside of your ego. In a creative world that’s increasingly centred around the self, around persona and visibility, how do you manage that? What’s your advice for surviving and creating without getting consumed by perception?

MT: I do think that spiritual practices that help you with your ego, and help you dismantle it, are so helpful to creative people. It can help you keep your mind on the work, and not on what you think the work is going to do for you, or how you think it will elevate you. You are not your book, and what people think of your book is actually none of your business. You put the book out into the world, and then let go of it and write another one, just keep moving. I also think that being a fan is a really wonderful ego-silencing practice. I’ve always been a huge fan of the art and artists that I love. I love going to a book conference as a reader more than a writer, [but] I’ll bump into other writers who are just having panic attacks because they’re like, ‘Who am I in this mass of authors?’ There’s no end to that type of mindset; it’s a sickness. The only thing that solves that problem is getting rid of ego and really feeling like it doesn’t matter if your book’s a best seller or not. It really doesn’t.

Also, just remind yourself that you’re not feeding hungry people. We’re writers. We’re so lucky. We’re not doing surgeries on people with brain tumours. Books do save lives, they are so important, but it’s just about holding it in the right place. An ego wants to make you believe that you’re the most important thing in the whole world, and you’re just not. I find it very relieving to know I’m not.

DS: What do you think a 25-year-old Michelle would make of your life now?

MT: I saw a meme about that recently that was like, ‘Oh, my younger self would be disappointed in me – good thing I don’t care what an alcoholic, mentally ill teenager thinks!’ [Laughs]. But truthfully, I think that young me would be totally impressed. I think that she would think I was cool.

The 25th anniversary edition of Valencia by Michelle Tea includes a foreword by Maggie Nelson, is published by Serpent’s Tail, and is out now.