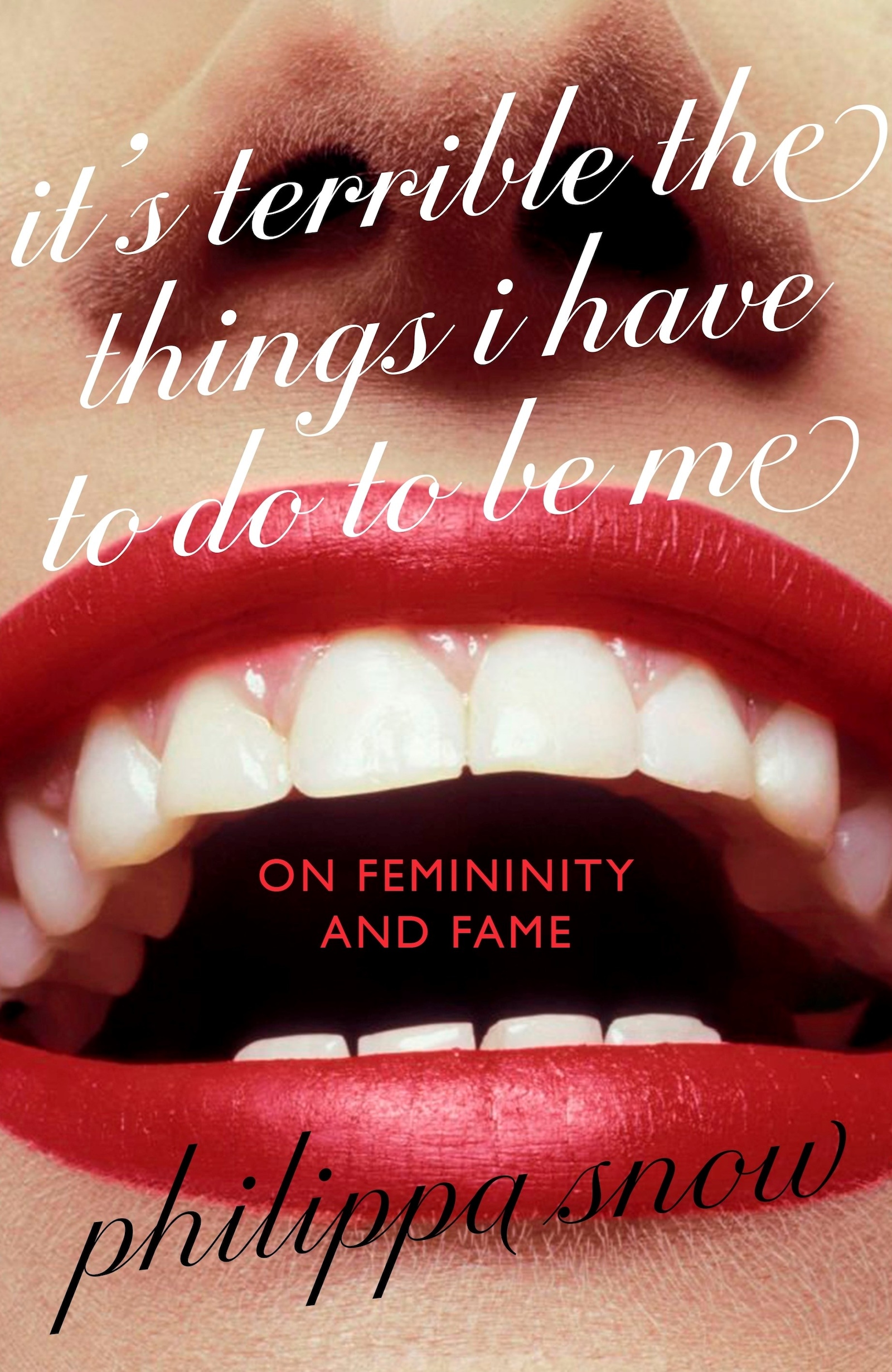

No writer weaves feminist art theory with celebrities quite like Philippa Snow. Known for Which As You Know Means Violence (2022) and Trophy Lives (2024), her latest book, It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me, takes a sharp, unflinching look at some of the darkest and most revealing moments in the lives of women in the spotlight, each caught between authenticity and artifice.

Through provocative pairings – Anna Nicole Smith and Marilyn Monroe, Lindsay Lohan and Elizabeth Taylor, Pamela Anderson and Caroline Cossey – Snow explores how these women mirror and shape one another across generations, examining how femininity is packaged, performed, commodified, and ultimately punished in the landscape of fame.

At once deeply personal and culturally expansive, Snow exposes the unbearable scrutiny women face under the ever-shifting boundaries of surveillance and consent, dissecting how their performance – both public and private – defines them. She’s less interested in moral judgment than in the contradictions of fame itself, each essay reminding us that to be famous is to be consumed, and that there is both an alluring beauty and agonising cost of being seen in a society obsessed with image. It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me asks, what does it cost to be authentically yourself in a world that punishes you for trying?

Below, Philippa Snow talks more about the book.

Jodie Hill: What led you to write this book?

Philippa Snow: I started thinking about a version of this book, genuinely, almost a decade ago. Writing about famous women has been something I’ve returned to over the years, for the reasons I outline in the introduction – very briefly, that I think celebrity women are interesting subjects of study because of the fact that they are, as US Weekly would say, just like us, but on a more spectacular scale. When I was first looking to sell the book, I was actually positioning it as a book of essays where each one was about the last year of a female celebrity’s life: after the fame, after youth and beauty, after the highs and lows. I was interested in seeing what we, as a culture, left these women with towards the end, and also how they had adapted to the changing parameters of fame over the years.

JS: Why did you choose to pair these women and write about them comparatively?

PS: It was my editor at Virago, Anna Kelly, who suggested the paired format. She had noticed a tendency towards writing about mirroring, splitting and pairs in my pieces about high-profile women, and wanted to bring that concept out. Also, a book entirely about death is a hard sell! This version of it is already quite dark, but that one would have been harrowing, I think.

“We’re finally crediting hot female pop stars with intention and intelligence, but it does unfortunately introduce yet another thing they’re expected to execute perfectly” – Philippa Snow

JH: Your previous books, while still covering celebrity culture, were very much focused on the art world. What is the connection between these previous books and It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me?

PS: All three books are about major transformations of the body and of the self. They are all about, to some degree, self-harm and sacrifice, and they all attempt to confer a kind of dignity on people who have taken extreme measures to define or redefine themselves. A lot of the art I enjoy is very dramatic, very startling – performance-heavy and centred around themes of sex, violence, gender, glamour, and altered psychological states. All of those things are part of the historic landscape of celebrity, as well. I’m not talking about stuff that happens in a gallery space, here, but I am, in a sense, talking about practitioners of an art form, even if it’s not an art form we usually take seriously in quite the same way.

JH: A lot of the women featured in your book came to fame either in the late 20th century or early 2000s. This period was generally new territory for fame in terms of consent and surveillance. Do you think that celebrities now are more self-aware and therefore less vulnerable than they were then?

PS: In the book, I talk a bit about one of the parities between Lindsay Lohan and Elizabeth Taylor being that each of them rose to fame during an era where the requirements of the job were shifting: Liz at the dawn of paparazzi coverage, and Lindsay in the first flush of that paparazzi coverage becoming dizzyingly extensive, thanks to outlets like TMZ. I think there is necessarily a period, whenever celebrity coverage enters a new phase or begins to rely on new apparatus, during which those being surveilled haven’t quite caught up to the rules yet, and this period can be particularly exposing for the subjects of the media’s (or the internet’s) attention.

Currently, being seen as winkingly self-aware is a huge boon for a famous person from a marketing perspective, and a wave of revisionist feminism aimed at tabloid coverage of women from the past – especially the recent past – has provided both fans and celebrities with a different roadmap for how the relationship between civilian and star ought to work going forward. Often, though, the issue with this revisionist feminism is that it asks the woman being spoken and written about to perform the role of victimhood ‘correctly’ to assure her redemption, when of course there’s no such thing as a perfect victim. This is a huge topic, obviously, and I don’t really speculate about the future of celebrity as an abstract construct in the book, because it’s less a work of journalism and more a bonkers, essayistic, vaguely impressionistic exploration of these women as near-mythic embodiments of certain cultural archetypes.

One relatively recent development, however, does seem to be that female stars are now being asked to perform feminism itself in the ‘correct’ way, too, which is how the internet ended up catching fire for about four days over a photograph of Sabrina Carpenter having her hair sort-of-pulled on the cover of her album. On the one hand, at least we’re finally crediting hot female pop stars with intention and intelligence, but on the other, it does unfortunately introduce yet another thing they’re expected to execute perfectly.

“The best celebrities tend to be people who have an innate sense of how they appear to others, and have a knack for redesigning themselves accordingly” – Philippa Snow

JH: In the past decade, many pop stars have been media-trained to be inoffensive and generally palatable. But with the latest revival of the indie-sleaze era and musicians like Charli XCX and Addison Rae, it seems there is demand for the ‘messy’ celebrity again. What do you think has led to this shift?

PS: I wonder if Instagram is behind this. Probably TikTok also – though, to be clear, I’m old enough to remember the first time what’s being called indie sleaze rolled around, so I don’t have a TikTok account. In Trophy Lives, I wrote about the idea that the advent of Instagram gave celebrities an opportunity to reclaim their images from the paparazzi, to some extent at least. There’s a level of intimacy implicit in our being shown images that stars have taken of themselves, even if that intimacy is completely ersatz, and their ‘authenticity’ is in itself a pose. That shift might have primed us for a return to mess, and might also have made a very controlled public image – something rigid and unmoving – seem suddenly outdated, sort of déclassé.

It’s also possibly connected to that recent reassessment of 00s surveillance culture. At that time, young women were being photographed falling out of cars and snorting coke without their consent, whereas now at least, as you say, this public messiness – whether real or staged – is a conscious choice. Is there something appealing, for a younger star, about restaging that era’s druggy, smeared-kohl aesthetic, but knowingly, and with the power dynamic shifted so that the ingenue herself is the one in charge?

“Young women were being photographed falling out of cars and snorting coke without their consent, now at least public messiness is a conscious choice” – Philippa Snow

JH: What role do you think photographers play in the rise or demise of a celebrity’s image? You touched on this briefly in your essay about Lindsay Lohan and her relationship with photographer Terry Richardson.

PS: The best celebrities – by which I mean the ones who are the best at being a celebrity, rather than those who are the most talented in a more conventional fashion – tend to be people who have an innate sense of how they appear to others, and have a knack for redesigning or refining themselves accordingly. In this sense, there’s a sort of conceptual crossover between being a photographer and being a famous person: both jobs are fundamentally about constructing an image. The Terry Richardson photographs of Lindsay Lohan that I write about in the book work so well, I think, because – setting aside the Terry Richardson of it all – there’s a shared vision at play in them. They enhance her most dangerous and most fatalistic-seeming qualities, and they make those qualities inextricable from her sex appeal. There’s a folie a deux vibe to them, which is sometimes what a perfect collaboration between a subject and a photographer most resembles – a shared madness, or a shared fever dream.

That’s what having a photographer working with a celebrity brings, I suppose, in contrast to a supposedly ‘real’ Instagram image. I hate that I’ve once again used images by Terry Richardson as a springboard for discussing this idea, but maybe, given how much of the book is about the effects of the patriarchy on women in the public eye, it’s apropos.

It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me by Philippa Snow is published by Virago and is out now.